Faculty Q&A: Fisher and Frey discuss generative AI and its implications for PK-12 education

When the debut of ChatGPT first sent shockwaves through public discourse in November 2022, Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey were among those whose curiosity was piqued. The two longtime research collaborators and professors in the San Diego State University Department of Educational Leadership (EDL) decided they ought to give the generative artificial intelligence chatbot a spin.

“Nancy and I pride ourselves on watching the horizon and seeing what’s out there that we need to be thinking about,” said Fisher, who chairs the EDL department. “When we first played with ChatGPT, it was like, ‘Oh, this is interesting, but I’m not sure of the implication.’ Within three or four months, however, it was very clear that generative AI would be a time saver for teachers and eventually students would have to learn how to use it.”

Fisher and Frey have since been conducting translational research on generative AI and its applications for the PK-12 classroom. They synthesize what is known about the technology and make recommendations to educators on how to proceed. Last year, they co-authored, “The artificial intelligence playbook: Time-saving tools for teachers that make learning more engaging” alongside education coach Meghan Hargrave. The second edition of this book will be published in May 2025.

Recently, the COE News Team sat down with Fisher and Frey to discuss implications, applications and why educators should embrace generative AI as quickly as possible.

When you first looked at this technology, did you immediately see it as a positive?

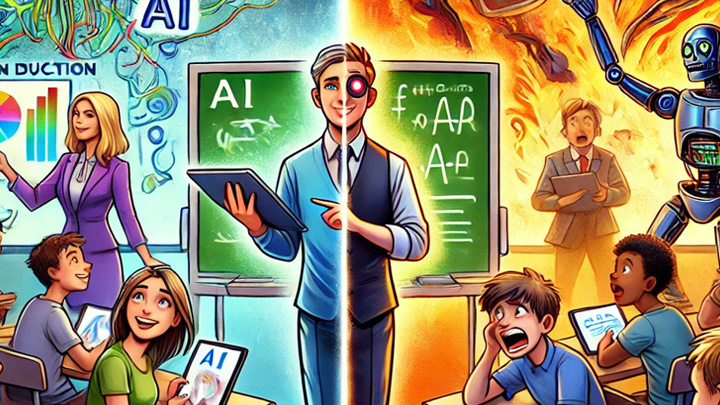

Nancy Frey: “There’s a phrase that there are boomers and doomers when it comes to AI. A ‘boomer’ is not generational, rather someone who sees lots of positivity and potential. Doomers are the ones saying, ‘Everybody’s going to spy on us and the robots are going to take over and kill us all.’ I think that we definitely lean more to the boomer side. We also have the sensibility — as current educators and leaders who have to make decisions — to think about how it can be used ethically. But we understand that in education, our charge is to prepare students for an unknown tomorrow, not for our own past. We have to be thinking about how to future-proof the students of today — and how to help leaders and teachers be able to do so."

What do you see as the most important near-term applications for AI in the classroom or at schools generally?

NF: ”I think, in terms of the adults in the classroom, there are two immediate applications. One is obviously around content generation — whether it’s lessons, materials, assessments and so on. The other is in being able to analyze data that may not appear to be related, but actually are. In other words, being able to do some pattern detection and some trend detection, especially among things that might not be totally obvious at first glance.

What would be an example of that?

NF: “One example is tracking student progress. It has been conventional practice that the way you look at student learning is who mastered something versus who didn’t. That’s often gauged through assessments of one kind or another. But it’s been more difficult from a data standpoint to really tease out who’s actually making progress — even if they didn’t hit mastery. Who are the kids increasing that trajectory of their progress versus who already knew this stuff before the unit got started and just sort of coasted? If we only look at mastery, and we don’t also look at progress, then it becomes really difficult to determine what’s actually working and what we should do more of.”

Douglas Fisher: "I’ll add one thing on the power of trend analysis. The early worry was that (AI) would get the trend analysis wrong. But right now, we’re seeing really strong pattern recognition in generative AI, and it’s faster. In fact, in our leadership program, we’re having aspiring school leaders enter their school data in generative AI to help them write their school improvement plans. Otherwise it would take them hours to analyze this data. Now, AI doesn’t write the school improvement plan for you. It doesn’t know your local context. But it’s really good at pattern recognition. That’s where I think teachers can really benefit. What are the trends in my class? Who needs what from me and what will I do next?”

What do you see as the implications from the student perspective?

DF: “There are all kinds of perspectives on this, from ‘it’s ruining critical thinking’ and all kinds of stuff. I take more of a realist view. This exists and you can’t put the genie back in the bottle. We have to teach students how to ethically use this. In education, we’re not good at technology adoption. The Internet was gonna ruin classrooms. TV was gonna ruin classrooms. We have to learn how to harness this, and we have a responsibility to teach students ethical, socially responsible ways of using it.

“I appreciate San Diego State saying, ‘The faculty recommendation is to tell students what level of AI use is expected or appropriate for this assignment, and then hold them accountable for that.’ I think the more interesting thing to talk about with students is how to teach them to analyze the credibility, validity of the output, then how to use that in a more generative dialogue — back and forth, back and forth. Nancy and I tell our students "use AI," show us the transcript so we see what part was yours and what part was generated by AI.”

What concerns you about generative AI in education?

NF: “I think that there’s a growing concern around equity as it relates to AI access. There is already a significant digital divide when it comes to who, as learners, are able to use AI and who are not. There was a fascinating study that was done here at San Diego State that linked AI usage to the number of devices that a person owned. The more devices that you had, the more likely it was that you were able to use AI. I think about students who, for example, might only have one device — typically a smartphone — and they’re sitting next to a student who has three different kinds of devices. Part of what we need to be doing in schools is not only making sure that we have policies that make a lot of sense to students and to teachers, but also that we're paying close attention to what that access to AI is.”

Your book came out almost a year ago, and this technology is changing so rapidly. Are you planning another edition?

DF: “As Ethan Mollick says, today’s AI is the worst AI that will exist in your lifetime. It’s changed a lot since the first edition, which is why we have the second edition coming out in May 2025. ”

In closing, what’s your recommendation to educators at this moment to get out ahead of this?

DF: “Start using it right now for simple things. Use it every day, because then you’ll start to find ways you can innovate with it.”

NF: “I would add to make sure that you're knowledgeable about what your district’s present policies and initiatives are around AI. You're hardly going to find a school district that doesn't have some kind of AI task force that has already been put together. If you’re not a part of that, that’s fine, but make sure that you know about them. All of us being a part of the conversation is really important.”